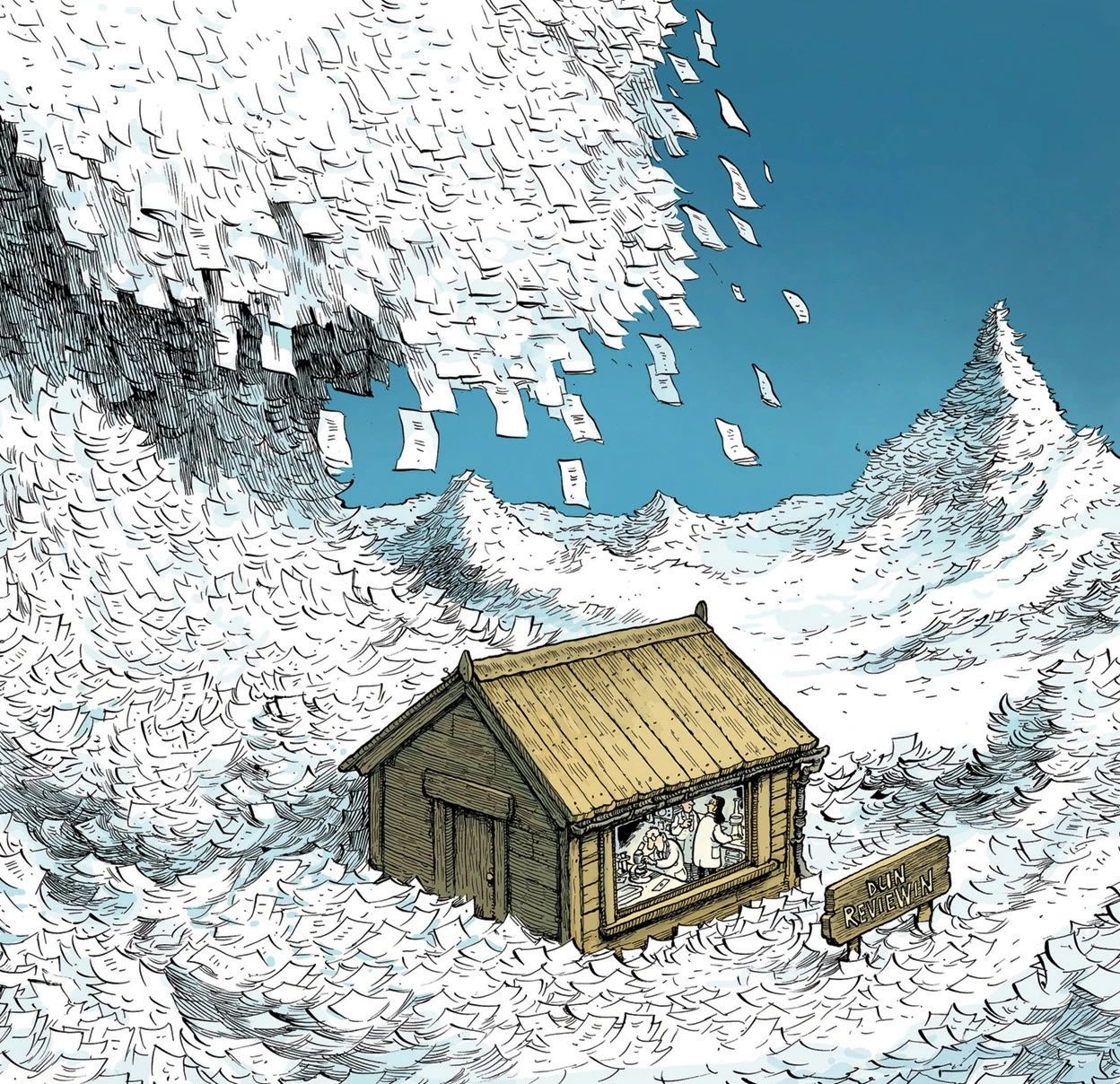

Peer Review on the Brink of Collapse: $450 for a Single Report? Scientists Are No Longer Willing to Work “for Love”

-

Even rewards of nearly €1,000 per day are no longer enough to attract enough experts to review projects. This is not an exaggeration but a real dilemma faced by top funding agencies. If even financial incentives fail, does this mean the peer review system is fundamentally broken?

A case in point is the European Southern Observatory’s (ESO) ultra-large telescope in Chile, equipped with the MUSE instrument, which allows researchers to probe the most distant galaxies. The device is so popular that during the October–April observation season, global demand for telescope time exceeded 3,000 hours — equivalent to 379 sleepless nights, in a season that lasts only seven months. Clearly, even if MUSE were a time machine, there would still not be enough time to satisfy everyone.

Traditionally, ESO assembled expert panels to select the most promising proposals from this flood of applications. But with applications skyrocketing, even seasoned reviewers are reaching their breaking point.

A Radical Experiment: Applicants Review Each Other

In 2022, ESO introduced a bold solution: delegate the review process to the applicants themselves. Any team wishing to apply for telescope time must also evaluate competing proposals. This “peer-to-peer review” model is gaining traction as a popular remedy for the chronic labor shortage in peer review. This is also being adopted in more and more research conferences in computer science domain.

Mounting Pressure and Declining Quality

The surge in academic publications has left journal editors struggling to find reviewers, and funding agencies like ESO face the same bottleneck. The strain on the system has produced two major consequences:

- Declining research quality – Poorly executed, error-ridden studies are slipping through, revealing that peer review is failing as a quality filter.

- Stifled innovation – The rigid and burdensome process often prevents bold, creative ideas from securing support.

In fact, criticisms of peer review are nothing new. Since its inception, the system has been attacked as inefficient, biased, and prone to cronyism. But dissatisfaction has intensified in recent years, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic triggered an explosion in manuscript submissions.

To address the crisis, stakeholders have experimented with new measures: compensating reviewers, offering clearer guidelines, and even proposing radical reforms, including abolishing peer review altogether.

A Shorter History Than You Think

Although widely regarded as the bedrock of modern science, today’s peer review model only became standard practice in major journals and funding bodies during the 1960s and 1970s. Before then, editorial decisions were often made by a small circle of experts or even by editors themselves based on personal judgment.

As public investment in science surged, so did the volume of manuscripts, forcing journals to adopt external review to avoid overwhelming a few key gatekeepers. Even today, peer review is far from standardized — it is a patchwork of practices varying across journals, disciplines, and funding bodies.

Yet the system now faces the same crisis as in its early days: too many submissions, too few reviewers. A 2024 survey of 3,000 researchers revealed that half had received significantly more review requests in the past three years.

Can Love Alone Power Peer Review?

Funding agencies and journals alike are searching for ways to encourage researchers to shoulder more reviewing duties and submit their reports more promptly.

Attempt 1: Non-Monetary Incentives

- Some journals improved transparency by publishing review turnaround times, slightly reducing delays, though mostly among senior scholars.

- Others created awards for prolific reviewers, but this backfired, as awardees tended to accept fewer assignments the following year.

- A widely supported reform is to recognize peer review contributions in formal research assessments. In an April 2024 survey by Springer Nature of over 6,000 scientists, 70% wanted review work to count toward career evaluations, though only half reported that their institutions already do so.

Attempt 2: Paid Reviews (A Longstanding Debate)

The ultimate incentive may be money, but paying reviewers has sparked decades of debate.

- Proponents argue it fairly compensates labor and recognizes the enormous value reviewers contribute. Psychologist Balazs Aczel and colleagues estimated that in 2020 alone, reviewers collectively provided over 100 million hours of unpaid work, worth billions of dollars if monetized.

- Opponents warn of conflicts of interest and perverse incentives, such as rushing reviews for pay. They also point out that many academics see reviewing as part of their salaried duties.

Frustration with providing free labor for profit-driven publishers has grown. James Heathers, a scientific integrity consultant, famously blogged in 2020 that he would only review for scholarly societies or nonprofit journals without charge. For commercial publishers, he sent invoices for $450 per review. Although invitations from major publishers dried up, requests from nonprofit outlets surged.

Mixed Results from Paid Review Experiments

Two journals recently published the results of their pay-for-review pilots, with starkly different outcomes:

-

Case 1: Critical Care Medicine

Reviewers were paid $250 per report. Acceptance rates for invitations rose modestly (48% → 53%), turnaround time shortened slightly (12 → 11 days), but review quality showed no improvement. The journal admitted it lacked the funds to sustain payments long term. -

Case 2: Biology Open

Run by the nonprofit Company of Biologists, this journal offered £220 ($295) per report and required responses within four days. Astonishingly, all manuscripts received initial decisions within seven business days (average 4.6), compared to the previous 38-day cycle. Review quality, according to editors, was maintained. Encouraged, the journal has decided to make the system permanent.

Meanwhile, even lavish offers may not suffice. Hanna Denecke of the Volkswagen Foundation in Germany noted that finding reviewers is becoming “extraordinarily difficult,” despite offering nearly €1,000 ($1,160) per day. At a London conference in June 2025, several UK funding bodies reported success with similar pilots, cutting decision times by half compared to traditional processes.

Beyond Payment: Structural Reforms

Addressing Bias Concerns

Some pilots split proposals into separate pools, ensuring reviewers assess only applications outside their group, preventing conflicts of interest.

A further advantage: distributing decision-making away from entrenched senior scientists, who sometimes act as gatekeepers blocking new entrants.

The Real Solution: Expanding the Reviewer Pool

Ultimately, many experts argue that the only sustainable fix is to enlarge the reviewer base. Most new submissions now come from emerging research nations, yet reviewers are still largely recruited from established Western academic circles. This imbalance must change.

Structured Peer Review

Elsevier piloted a system in 2022 requiring reviewers across 220 journals to answer nine structured questions (e.g., “Is the statistical analysis valid?”). Results showed improved reviewer consistency — agreement rose from 31% to 41%. The method also encouraged reviewers to acknowledge gaps in their expertise, allowing editors to bring in additional experts. Today, over 300 Elsevier journals employ structured peer review.

Transparency as an Incentive

Advocates of transparency propose two measures:

- Publishing peer review reports alongside final articles.

- Encouraging reviewers to sign their names.

Supporters argue this elevates the status of review work and motivates higher-quality feedback. As Stephen Pinfield observed, “If reviewers know their reports will be public, they will work harder to ensure quality.”

Conclusion

Peer review is under immense strain: too many manuscripts, too few willing experts. Efforts to address this, whether through non-monetary rewards, direct payment, or structural reforms, have produced mixed results. Yet the central dilemma remains: science continues to generate more knowledge than the current system can reliably evaluate.

The future of peer review may hinge not on whether reviewers are paid, but on whether the system can adapt — by broadening participation, increasing transparency, and reimagining how scientific quality is judged in the first place.

Reference: Nature – Is peer review collapsing?

-

Thanks for sharing this article from Nature!