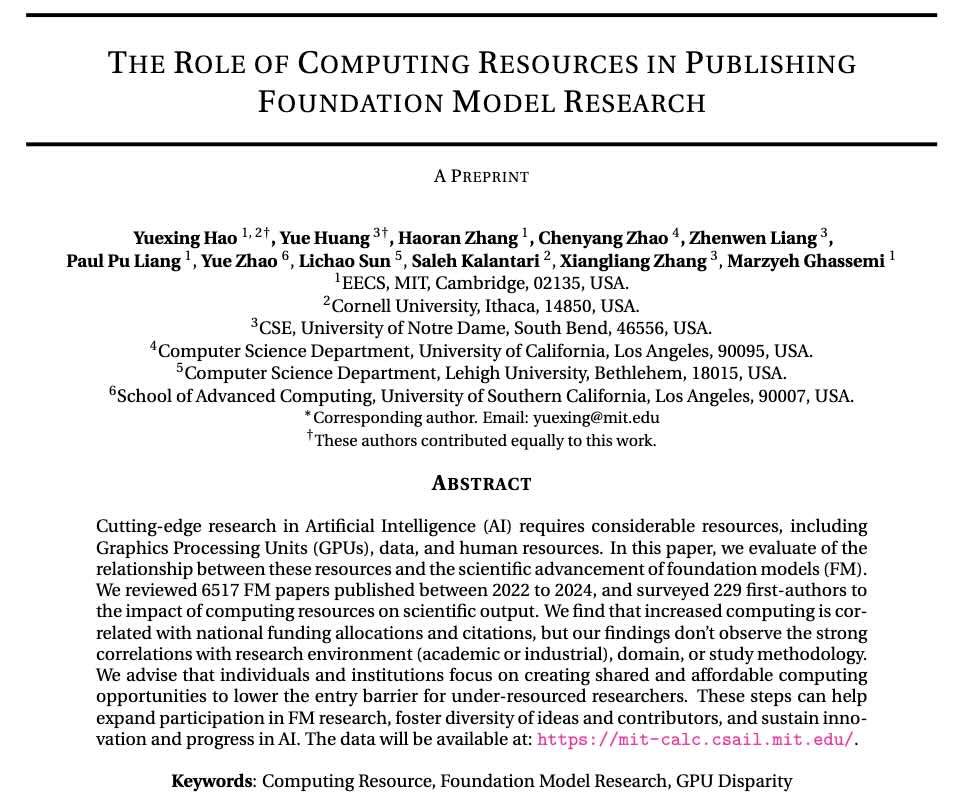

[image: 1764333195142-screenshot-2025-11-28-at-13.32.51.png]

On the night of November 27, 2025, computer-science Twitter, Rednote, Xiaohongshu, Reddit and WeChat group lit up with the same five words:

“ICLR can open the box.”

Within hours, people were pasting a one-line URL template that did the unthinkable:

Plug in a paper’s submission ID

Plug in a reviewer index

Hit enter

…and OpenReview’s backend obligingly returned the full, de-anonymized profiles of reviewers, authors, and area chairs, not just for ICLR 2026, but for any conference hosted on the platform.

Double-blind review, the sacred cow of CS publishing, had just become Naked Review.

This post reconstructs the timeline, surfaces what the community actually did with the leaked data, and asks some uncomfortable questions about how we secure our review infrastructure — and how we evaluate research and researchers in the first place.

1. What actually broke? The one-parameter bug

At the center of the storm was a single API endpoint:

/profiles/search?group=…

This endpoint is supposed to support harmless features like “show all reviewers in a program committee.” Instead, it quietly accepted a group parameter pointing to any OpenReview group — including the internal groups that encode author lists and reviewer assignments for each submission.

The effect was a textbook broken access control failure:

No authentication was required beyond being a random person on the internet.

Changing only the group name in the URL flipped you between:

…/Submission{paper_id}/Authors

…/Submission{paper_id}/Reviewer_{k}

…/Submission{paper_id}/Area_Chair_{k}

For each of these, the API returned raw JSON profile objects: names, personal and institutional emails, affiliations and job history, ORCID & DBLP links, pronouns, sometimes year of birth — and even a relations field that spelled out who someone’s PhD advisor was.

Data that many reviewers had entrusted to a private profile backend was suddenly being sprayed to anyone who could edit a URL.

This wasn’t hacking. This was “copy & paste from a chat message.”

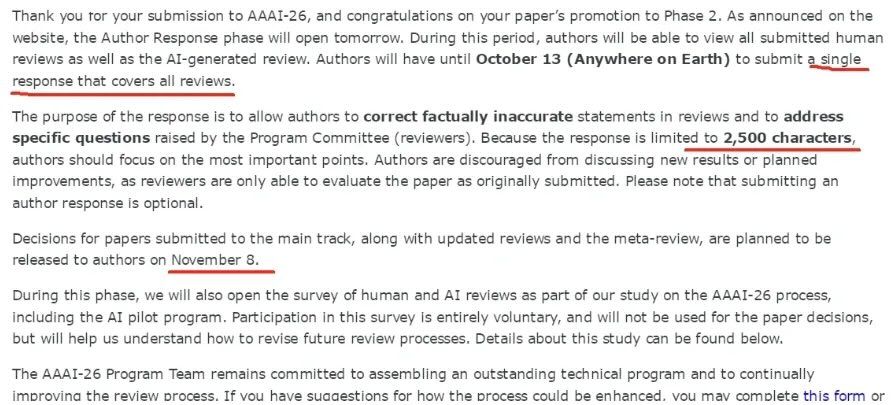

[image: 1764333397227-screenshot-2025-11-28-at-13.36.25.png]

2. Timeline of an academic meltdown

The dates below are approximate, blending OpenReview’s official statement with community-collected evidence.

Early November: the invisible window

~11 November (Beijing time) – Multiple users notice that profile data can be queried via the profiles/search endpoint with no authentication as long as you know the group name.

12 November – At least one researcher sends a responsible disclosure email to security@openreview.net, documenting the bug with reproducible examples for ICLR 2026 submissions. According to screenshots, they never receive a reply.

For roughly two weeks, OpenReview is effectively an unlocked cabinet of identities across ICLR, NeurIPS, ICML, ACL, and other venues.

We have no public log of who probed the bug during this period.

November 27 (morning, US / evening, China): the blast radius becomes visible

10:09 EST – The ICLR 2026 Workflow Chair formally reports the issue to the OpenReview team.

10:12 – OpenReview acknowledges and begins investigation.

11:00 / 11:08 – Fixes are rolled out to api.openreview.net and api2.openreview.net.

11:10 – ICLR program chairs and the workflow chair are notified that the vulnerability is patched.

The rapid one-hour response on the day of the report would look heroic… if not for the two-week head start.

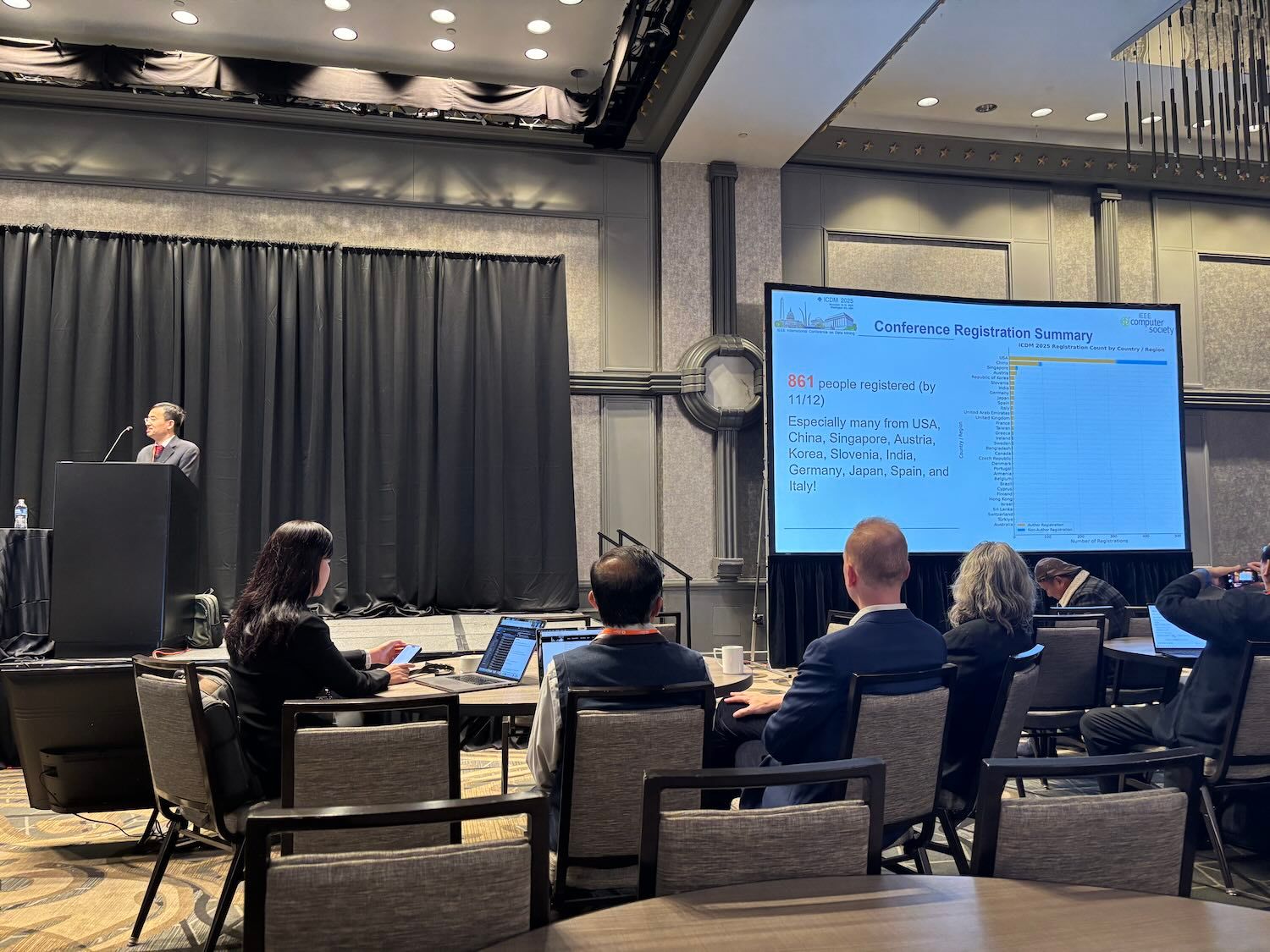

[image: 1764333285727-screenshot-2025-11-27-at-18.07.33.jpg]

November 27–28: “ICLR = I Can Locate Reviewer”

By the time the fix rolls out, screenshots and URL templates are already circulating:

A viral Xiaohongshu post shows a green chat bubble with three URLs:

/Submission{}/Authors

/Submission{}/Reviewer_{}

/Submission{}/Area_Chair_{}

and cheerfully tells readers: “Just swap the curly braces for paper ID and reviewer index.”

Within hours, people are:

Locating their own reviewers.

Cross-checking infamous reviews (like the “40 weaknesses, 40 questions” copy-paste review that hit multiple papers).

Identifying a “hero” reviewer who slapped a 0 (strong reject) on an obviously AI-generated nonsense paper that otherwise had two glowing 8s.

Chinese WeChat and Rednote threads coin the meme:

ICLR = I Can Locate Reviewer.

[image: 1764334235414-g6y8kjewgaaet9p.jpeg]

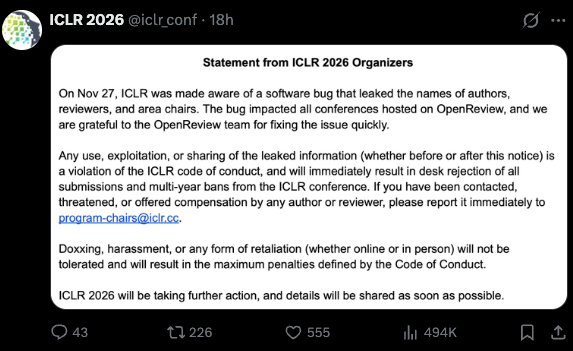

November 27: Official statements land

Two formal statements arrive in quick succession:

OpenReview publishes “Statement Regarding API Security Incident – November 27, 2025,” acknowledging:

A bug in profiles/search that exposed normally anonymous identities (authors, reviewers, area chairs) across venues.

A one-hour patch window after the ICLR report.

Ongoing investigation into API logs and commitments to notify affected users and venues.

ICLR 2026 organizers issue their own statement:

Confirming the leak of names of authors, reviewers, and area chairs.

Declaring that any use, sharing, or exploitation of the leaked data violates the code of conduct.

Threatening immediate desk rejection and multi-year bans for violators.

Shortly after, a Reddit post reports that at least one paper has already been rejected because the authors publicly shared their OpenReview page (which now implicitly ties them to de-anonymized reviewers).

November 28+: The long tail

Even after the patch, the incident keeps mutating:

Some reviewers report receiving direct emails from authors asking for higher scores — or even offering money in exchange for a rating bump.

Others discover that their harshest reviewer is:

An author of a direct competitor paper, or

A near-field outsider with little subject-matter expertise.

Social media fills with dark jokes about next week’s NeurIPS hallway conversations degenerating into “mutual desk-rejection showdowns.”

Meanwhile, people start to ask a scarier question:

If this was exploitable for at least two weeks — and maybe longer — how many complete crawls of the OpenReview database have already been taken?

3. What leaked — and how people mined it

The depressing answer: almost everything that was never supposed to leave the backend.

From reconstructed JSON dumps:

Identity & contact

Full names (including “preferred” name variants), multiple emails, personal vs institutional addresses, and social identifiers like ORCID and DBLP.

Career history

Per-position records like “PhD student at X from 2017–2021” or “Associate Professor at Y since 2022.”

Relationships

Explicit relations entries for “PhD advisor,” collaborators, and more.

Demographics (sometimes)

Pronouns, year of birth, and other fields some users filled in.

On top of static profile data, the fact that the group name encodes the role meant that you could trivially pivot from:

“Who reviewed my paper?” to

“Who reviewed this other paper I care about?” to

“What’s this person’s full reviewing pattern across conferences?”

Armed with this, different corners of the community did very different things.

3.1 Naming & shaming

The most sensational stories focused on individuals:

The infamous “40 weaknesses + 40 questions” reviewer turned out to be one mid-career academic who had apparently reused the same mega-template across multiple submissions. Their profile — department, title, advisor — was trivial to pull up.

The “hero” who torpedoed an AI-generated nonsense paper with a 0 score was identified as a postdoc in logic and verification, making the critique feel poetically well-qualified.

Responsible outlets blurred names and emails. Private chats… did not.

In effect, the bug enabled targeted doxxing of both “villain” and “hero” reviewers — something both sides never agreed to.

3.2 Amateur meta-science (and casual bias)

Others immediately used the data for ad-hoc analytics:

Aggregate plots of average score by country of affiliation, with hot takes like “Korean and Russian reviewers are strictest” and “Chinese reviewers are soft.”

Lists of the “most lenient” and “most strict” reviewers, computed from their ICLR score histories.

Spot-checks revealing papers reviewed by people well outside their technical field, reinforcing longstanding complaints about reviewer matching.

Unsurprisingly, much of this “analysis” was shaky: small sample sizes, confounded by topic, seniority, and assignment policies — but irresistible as gossip fodder.

3.3 Personal detective stories

At the micro level, individual authors used the leak to reconstruct grievances:

One author discovered that their most negative reviewer was literally an author of a competing submission.

Another confirmed that the reviewer who ignored their rebuttal for a week — only to maintain a harsh score — was a near-neighbor in the same subfield with overlapping research agendas.

The natural temptation was to escalate to program chairs. But the paradox is brutal:

Under double-blind rules, you were never supposed to know who reviewed you.

To complain, you’d have to admit you queried leaked data, violating the very code of conduct that the chairs are obligated to enforce.

Catch-22, peer-review edition.

[image: 1764443383595-screenshot-2025-11-28-at-09.35.25.png]

4. From glitch to platform: the rise of shadow mirrors

Fixing the API didn’t make the data disappear.

Within a day, a new domain began circulating: openreview.online.

Its landing page branded itself as “ICLR Review Radar”, with tabs like:

“Most strict”

“Most lenient”

“Most volatile”

“Most disputed papers”

“Frequent authors”

and a tagline along the lines of:

“Stats from review JSON: scores, confidence, text signals, and contention.”

In other words, someone had scraped a large chunk of the leaked review data, built a full analytics front-end, and was now offering public leaderboards of reviewer behavior.

Even if the site gets taken down (and at times it already shows empty tables), the message is clear:

Once a dataset of this sensitivity leaks, you don’t get the genie back in the bottle.

Shadow copies, private dashboards, and offline archives will persist long after the official platform is patched.

The academic community now has to live in a world where:

Reviewer identities and behaviors may already be known to actors we can’t see.

Every future “suspicious pattern” or rumor can point back to this leak, whether or not it’s actually grounded in data.

5. What this says about security in peer-review systems

At a purely technical level, the OpenReview incident is a case study in several classic API security failures:

Broken object-level authorization (BOLA)

Access to sensitive objects (profile records) depended entirely on the “shape” of the URL, not on the caller’s identity or rights. This is one of the top categories in modern API security taxonomies, precisely because it tends to be missed in fast-moving product teams.

Lack of least privilege

The profiles/search endpoint clearly had more power than any public endpoint should have. A strict design would:

segregate public vs private profile fields,

require authorization tokens with scoped permissions, and

rate-limit or block bulk cross-venue queries.

Weak vulnerability-response pipeline

If the leaked emails are accurate, security-team mail about this exact bug sat unanswered for over two weeks. That’s not just an honest mistake; it’s a process failure.

This is exactly the kind of situation “security by design” and “privacy by design” principles were invented for: start from the assumption that data is sensitive and APIs are hostile, and build tooling, threat-models, and processes accordingly.

“But OpenReview is open…”

There’s a deeper tension here:

OpenReview’s mission is to make the review process more transparent.

Yet that transparency was never supposed to extend to de-anonymizing people mid-process.

Openness is not a substitute for access control. If anything, open data models require stricter design and testing because the system’s attack surface is larger and better documented.

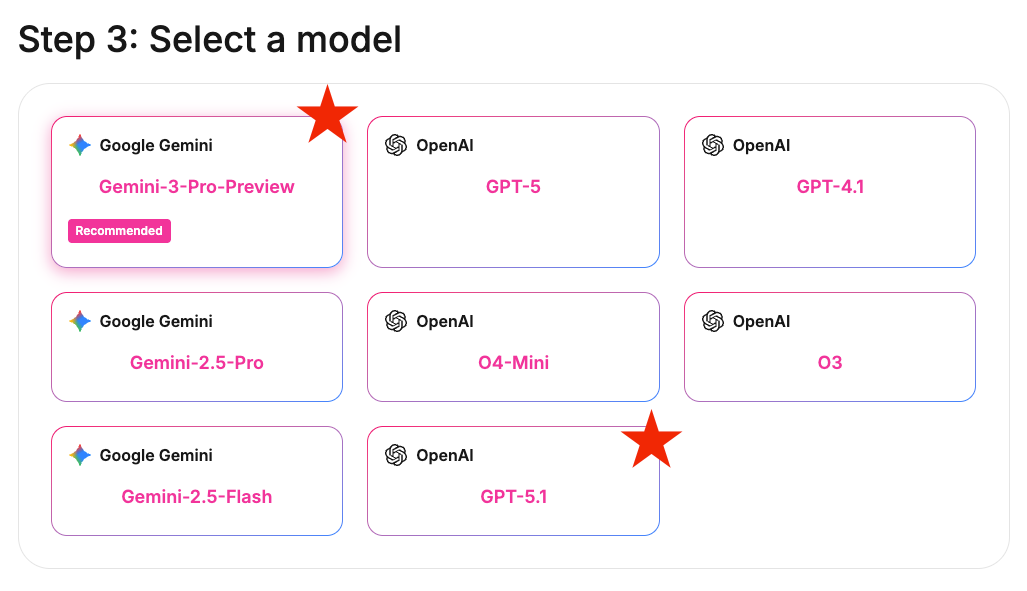

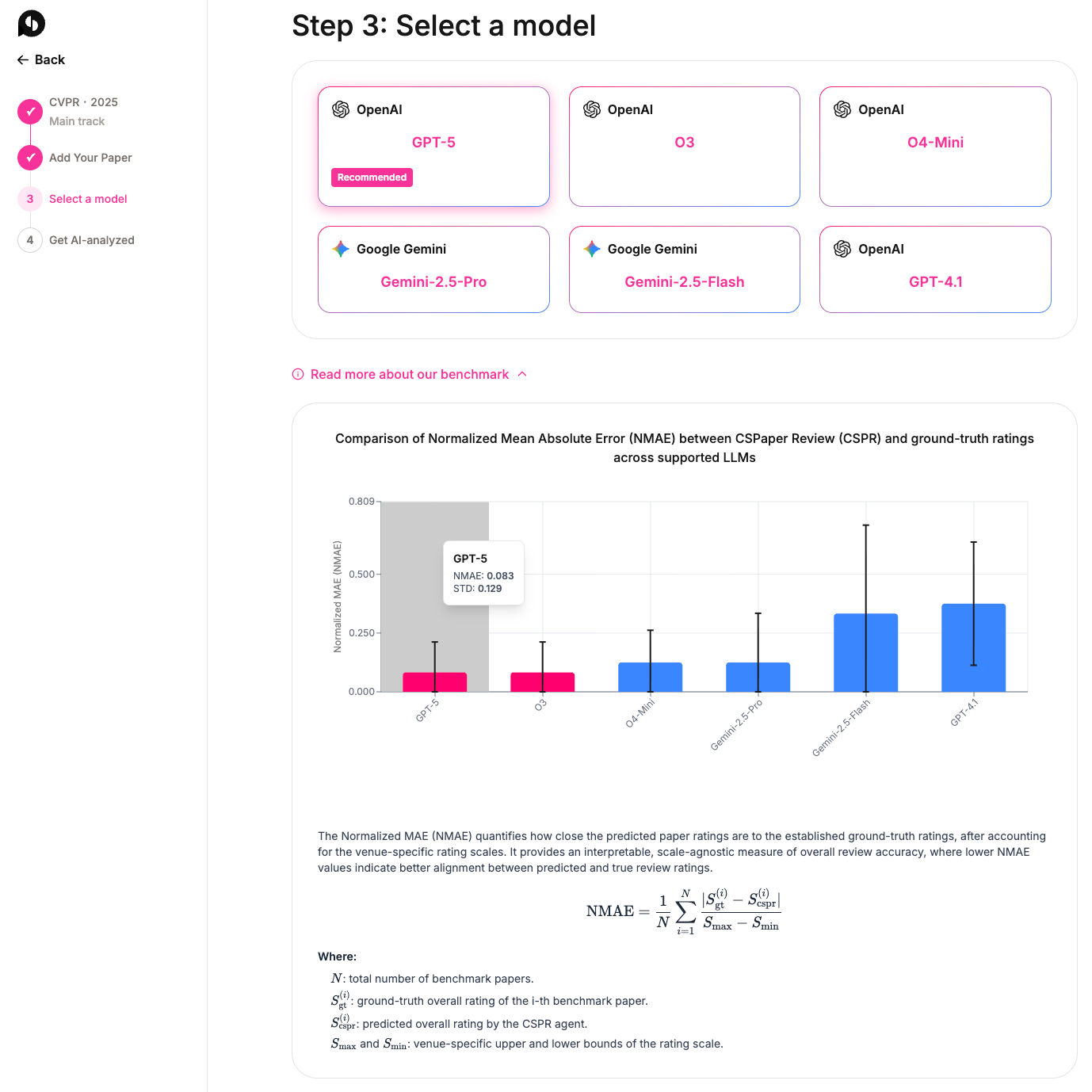

CSPaper and privacy-first design

Our AI-assisted review platform CSPaper.org have had to grapple with security and privacy from day one, simply because researchers are understandably nervous about sending preprints into any opaque LLM system.

As a result, CSPaper’s public messaging leans heavily on guarantees like:

“Privacy and security first.”

Papers processed under enterprise-grade agreements with LLM providers, with contractual guarantees they aren’t used to train models.

User-level control to delete past reviews and data at any time.

Whether any particular platform lives up to its promises is always an empirical question, but the mindset matters:

Treat papers and reviews as sensitive artifacts.

Design for confidentiality and explicit consent.

Assume adversarial misuse, even if 99% of your users are academics with good intentions.

Peer-review infrastructure like OpenReview, EasyChair, MS CMT, and new AI-native systems can’t afford to treat security as an afterthought bolted on after “feature complete.” In 2025, they are critical infrastructure.

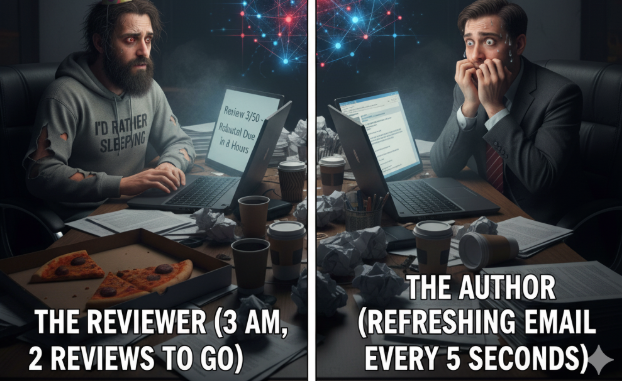

6. Beyond the breach: what are we actually evaluating?

Once you decouple the drama from the data, the OpenReview leak forces us to ask a tougher question:

What exactly are we evaluating — papers, or people?

The community’s immediate reaction was telling:

Lists of “strictest reviewers,” “lenient reviewers,” and “most controversial papers.”

Polarized narratives:

“Reviewer Z is lazy and used AI to mass-produce reviews.”

“Reviewer S is a hero for nuking that nonsense paper.”

Hot takes about which countries are “harshest” or “softest.”

All of that shares a common pattern: it treats individuals as the primary unit of analysis, not the structural conditions that produced their behavior.

Yet the underlying problems are systemic:

Reviewer overload and mis-match

Many reviewers are buried under dozens of reviews, often outside their narrow expertise. Given that, is it surprising that some reach for AI tools or generic templates?

Binary, high-stakes outcomes

Top-tier CS venues still turn a handful of 1–10 scores into career-defining accept/reject decisions. It’s rational for authors to obsess over “who killed my paper?” when each rejection hits grants, promotions, and visas.

Opaque assignment and escalation

Authors have little visibility into how reviewers are selected or how bad-faith reviews are handled. Grievances fester because there is no trusted channel to reconcile them.

Evaluation of researchers by venue logos

Hiring and tenure committees still overweight where you publish rather than what you publish. In that world, the identity of a negative reviewer can feel like the identity of someone who just voted against your job.

The OpenReview incident doesn’t create these pathologies; it merely illuminates them with an unflattering backlight.

Towards healthier evaluation criteria

If we don’t want every breach to devolve into witch-hunts and revenge fantasies, we need to change what we care about:

For papers

Richer, multi-dimensional evaluation beyond a single accept/reject: reproducibility badges, open-source artifacts, post-publication commentary.

More weight on long-term impact (citations, follow-up work, adoption) rather than one-shot committee votes.

For researchers

Hiring and promotion dossiers that emphasize contributions (methods, datasets, systems, community service) over venue counts.

Recognition and reward for high-quality reviewing, mentoring, and stewardship — not just for flashy first-author papers.

For reviewers and chairs

Structured rubrics and training that set expectations for rigor and tone.

Accountability mechanisms that don’t rely solely on anonymity: e.g., confidential meta-review by senior chairs, or optional signing of reviews, supported by clear anti-harassment protections.

AI-assisted tools — including platforms like CSPaper — can help by:

Providing rubric-aligned “first-pass” reviews that chairs can use to triage or sanity-check human reviews.

Giving junior researchers practice with realistic feedback before they face the roulette of a real CFP.

But tools are only useful if we pair them with healthier incentives.

7. Where do we go from here?

The OpenReview API fiasco is, on its face, a security bug.

But at a deeper level, it’s a mirror:

It shows how brittle our trust in double-blind review really is.

It exposes how quickly we slide from “protect reviewers” to “hunt reviewers.”

It confirms that we’ve built careers, grants, and lab hierarchies on top of systems that weren’t engineered — or resourced — as critical infrastructure.

In the short term, we must:

Treat the leaked data as toxic: don’t share it, don’t build new leaderboards on top of it, and don’t target individuals.

Demand transparent incident reports and process changes from platforms like OpenReview.

Push conferences to audit their security and response pipelines before the next cycle, not after.

In the long term, we need to stop pretending that fixing a URL parameter restores the status quo ante.

The real challenge is to design:

Secure, privacy-respecting infrastructure that assumes attackers, not just absent-minded grad students.

Evaluation frameworks that judge research on its substance and track record, not on the whims of whichever anonymous reviewer’s ID happened to be plugged into a buggy API.

Otherwise, we’ll keep playing the same game every year:

Blind review in theory.

Naked review in practice.

And a research community that never quite decides whether it’s evaluating ideas — or the people unlucky enough to shepherd them through a leaky, overburdened system.

🚀 Now Live: Our AI-powered paper review tool is available in beta! Perfect for CS conference submissions — get fast, targeted feedback to improve your chances of acceptance.

🚀 Now Live: Our AI-powered paper review tool is available in beta! Perfect for CS conference submissions — get fast, targeted feedback to improve your chances of acceptance.